Innovators.

Entrepreneurial.

Ambitious.

This is how Albertans have long described themselves, a story often centred around our successful development of the oil sands, Alberta’s most consequential bet.

But now the province is faced with a difficult question to reconcile: is this who we are or just who we were?

This question will be answered one way or the other, whether we respond to it directly or not. Quite simply, some forces are bigger than Alberta. The question we should be asking ourselves is, do we want to dictate our future, or have our future dictated to us.

Climate change and the global focus on emissions and sustainability is one of those forces. The recent UN Climate Change Conference (“COP ‘26”), where delegates from all over the world came to set a path of action to decrease emissions, serves as just one reminder.

While Alberta doesn’t get to decide whether or how other jurisdictions, investors, or consumers move forward, we do get to decide how we respond.

Are we the innovators and problem-solvers we claim we are, ready to lean into the next great challenge or are we spectators in a game we would prefer not to play?

To be sure, there is and has been great work taking place across Alberta on climate action, especially in the traditional energy industry. The oil and gas industry has made major headway to decrease its emissions intensity; it is the largest investor of clean technology in Canada and has built the world’s largest Carbon Capture Utilization and Storage (“CCUS”) transportation network which, in essence, captures harmful carbon emissions and safely transports and stores them to limit their consequences.

While this is important and essential work, there is a much bigger opportunity on the horizon for Alberta.

The global challenge

Decreasing emissions quickly enough to stave off the most harmful effects of climate change will require reducing emissions from activities that produce them (e.g. driving a car; heating our homes; producing energy; and raising cattle)–an enormous challenge, of which few truly appreciate the scope and complexity–as well as direct air capture, which involves removing emissions from the atmosphere (like a giant air filter).

This latter strategy, sometimes called “negative emissions”, is considered increasingly central to beating the clock, yet little progress has been made to enable it in a way that is scalable or cost-effective enough to move the dial.

As The Economist recently noted, “If negative emissions are to play a role in policy, much more needs to be done to make them practically achievable.” As they put it, emissions removal technologies remain “at best, embryonic.”

The opportunity for Alberta

Now is the time for Alberta to be very Albertan once again. We need to take bold steps to solve the world’s most pressing challenge–the need for food, goods, and energy on a planet that cannot withstand the emissions currently associated with them.

We could easily rationalize our way out of it– the risk, the cost, the unknown. Or, we can recognize the possibility of leading the charge to transform the irrational into the practical.

What is often forgotten in retelling the story of Alberta’s oil sands is how ridiculous the idea sounded at the time–and the staunch opposition to the project received from many. First it was thought impossible, then cost-prohibitive, and now oil sands production is not only feasible, but offers some of the only oil on earth with a path to net-zero. A similar story could prove true for negative emissions.

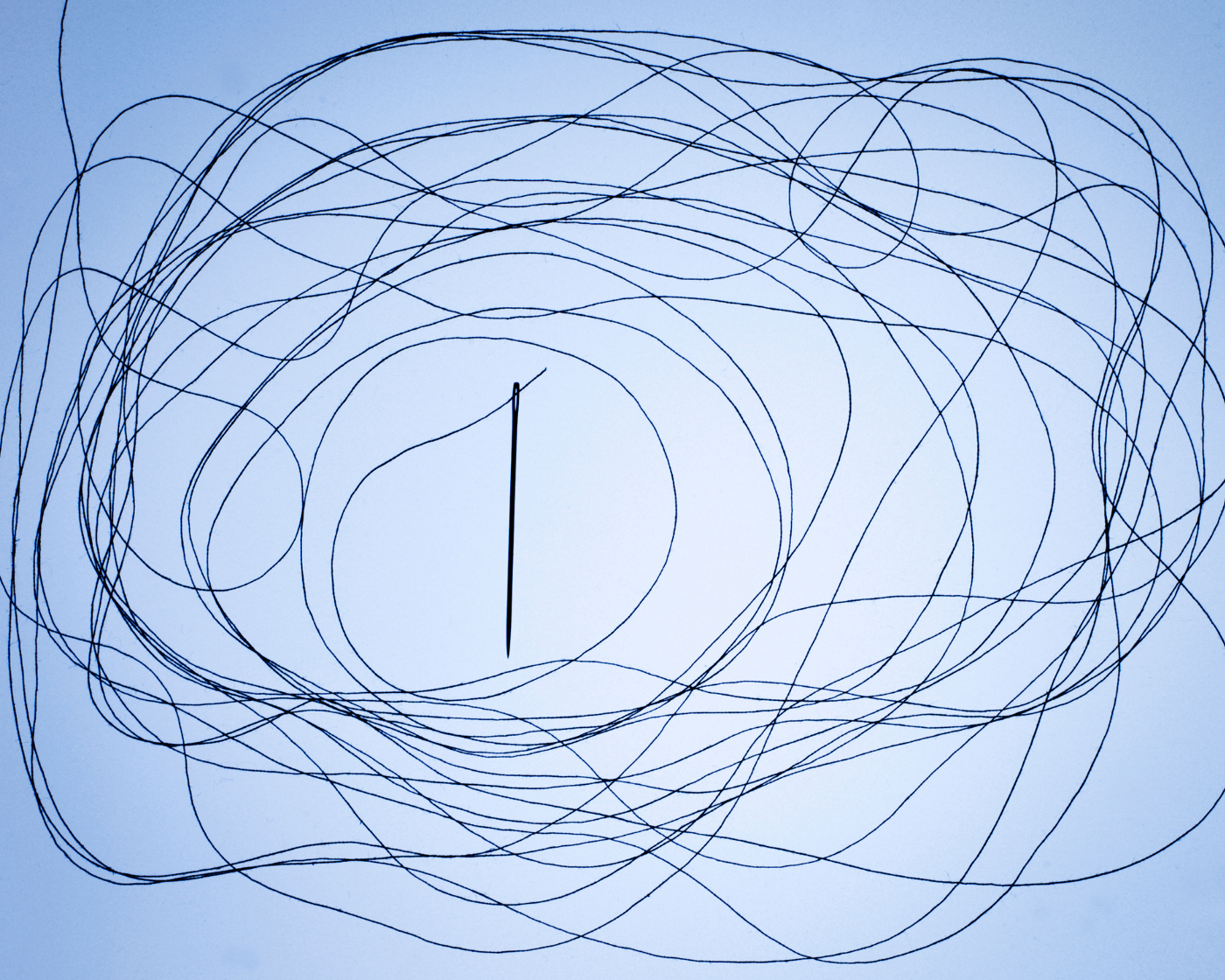

Revolutionary ideas rarely sound practical. Burt Rutan said, “Revolutionary ideas come from nonsense. If an idea is truly a breakthrough, then the day before it was discovered, it must have been considered crazy or nonsense or both–otherwise it wouldn’t be a breakthrough”.

Developing the oil sands was the epitome of revolutionary nonsense: “a daring venture into an unknown field”, a field which at the time could have been described as “embryonic”.

This time, Alberta is not starting from square one. We already have the experience and agility to become competitive in negative emissions technologies: familiarity and use of existing technologies like CCUS, individuals with deep knowledge of energy, emissions, and clean tech, as well as vast amounts of land for carbon storage and a strong underlying incentive–an abundance of valuable hydrocarbon resources to tap into in new ways that limit emissions. In fact, many oil and gas facilities today already employ a version of emissions reduction technology on a smaller scale.

To tackle the global challenge, and enact real, world-changing progress on negative emissions technologies, we’ll require a full-systems, all-of-the-above, approach.

As such, this is far bigger than any individual business or even industry. This is about building a province-wide culture, and the policy framework, required to propel breakthrough change in this space.

A big idea

So what exactly could this look like?

One “big idea” that would match the spirit of this ambition: Alberta could become the global centre for excellence for negative emissions technologies, processes, and tracking and authentication, carving our own path so that while the world focuses on net-zero (i.e. remaining emissions are “cancelled out” by emissions removal), Alberta sets its sights on enabling net-negative (where remaining emissions are more than cancelled out by emissions removal). This could be game changing for the discussion around our natural resources as well.

This big idea–or “moonshot”–would both signal to the world Alberta’s investment in the broader economic transformation taking place, and establish the province as a leader within it.

Furthermore, policies that drive not just fewer emissions but net-negative emissions opens up a differentiating factor for Alberta as a destination for energy investment. This would anchor Alberta at the heart of Canada’s “living lab” for the next wave of technological advancement.

What it will take

While good policy will be essential, equally so will be our willingness, as a province, to be a little “nonsensical.”

To define ourselves as entrepreneurs means we must embrace the other side of the coin–the discomfort, grit, and failure–required to make a crazy idea into a no-brainer solution.

The first and most essential component of progress is to create the environment–physical spaces, political norms, and the ambitious spirit–necessary for big ideas to be raised, collaboration to be commonplace, and an endless loop of trial-and-error to be accepted. It is about making space for the big, bold, and risky–that very foundation upon which Alberta was, in many ways, built and defined.

Second is speed. Building and improving upon negative emissions technologies should be tackled with the urgency of an election cycle but with the foresight of future generations. The clock is ticking.

Ultimately, Alberta should be the place where nonsense ideas are made into reality so often that it becomes a part of the fabric of who we are as Albertans. Perhaps with this, ,when we look back one day on previous breakthroughs, we will have once again forgotten how crazy any of these big ideas once were.

Alicia Planincic is an Economist at the Business Council of Alberta. She plays a crucial role in policy research and advocacy to make Alberta a better place. She brings experience in data analytics, a passion for effective prose, and a fresh perspective of economics.