We are surrounded by technical achievements — often near-miraculous, even if they may get taken for granted. The electricity grid that delivers a safe, constant and predictable stream of on-demand energy. Communication systems that allow real-time conversations with people on the other side of the earth. Networks of food delivery that allows us to enjoy fresh, safe, and relatively inexpensive produce in all seasons.

Each of these ‘miracles’ actually represents a complex system that came into being only through the concerted efforts of a broad range of actors. Underpinning that coordinated action is, more often than not, government policy.

Now, we face a new set of challenges around energy transition, emissions reduction, and the ongoing wellbeing of our fellow human beings. Policy will be at the root of decisions made about what actions get taken in this brave new world. Policy can be used to shape behaviour: of consumers, of markets, of producers, of investors, of competing jurisdictions. It provides both a vision for the future and the set of rules to be followed in getting there. As such, it is the foundational piece that underlies decisions about the complex systems surrounding a successful energy transition.

But how, exactly, does the government do that? What are the tools at its disposal? And what actions can a group such as the EFPC request the government take?

To answer this question, we developed a list of government policy levers that could be useful as part of the energy transition, and specifically in helping drive investment into innovation and infrastructure:

Vision: By providing vision and direction at a high level through strategies, goals, targets, or roadmaps, government can show enduring support and provide predictability and stability. The recently published federal hydrogen strategy and the small modular reactor (SMR) roadmap are clear examples.

Economic tools: The government is in a unique position to direct fiscal resources — its own or that of others — towards areas where it wants to incentivize development. Economic tools include direct financial support, procurement (the federal government alone procures over $20 billion per year of goods and services), fiscal policy measures, and making capital available to entrepreneurs — such as through the Canada Infrastructure Bank.

Asset planning: The government can use its power to influence the development and deployment of different classes of assets, including people, physical infrastructure, and natural assets. In its Healthy Environment, Healthy Economy plan published in December 2020, the federal government promised to conduct the first-ever national infrastructure assessment to identify needs and priorities for the supportive assets and infrastructure that will underlie the energy transition.

Regulatory approaches: These are the rules created by government that individuals and organizations — companies, investors, even the government itself — must abide by. They include regulation of capital markets and regulation of GHG emissions, but also land use regulations, royalty schemes, and other rules that shape market and policy agendas.

Market development: Domestic and international market receptivity can be shaped by government actions and agreements, such as international trade agreements, export market development, and creating opportunities to stimulate domestic demand for certain products.

Quality assurance: There is a role for government in boosting confidence in the quality and acceptability of products and technologies. These may come in the form of emissions standards (such as methane emissions standards), performance standards (such as for automobiles), or endorsement of specific certification schemes (as with Canada’s several forestry performance management certification options).

Finally, there are a number of policy levers that don’t fall neatly into the categories above, including research and commercial collaboration, collecting and disseminating data and information, and convening stakeholders.

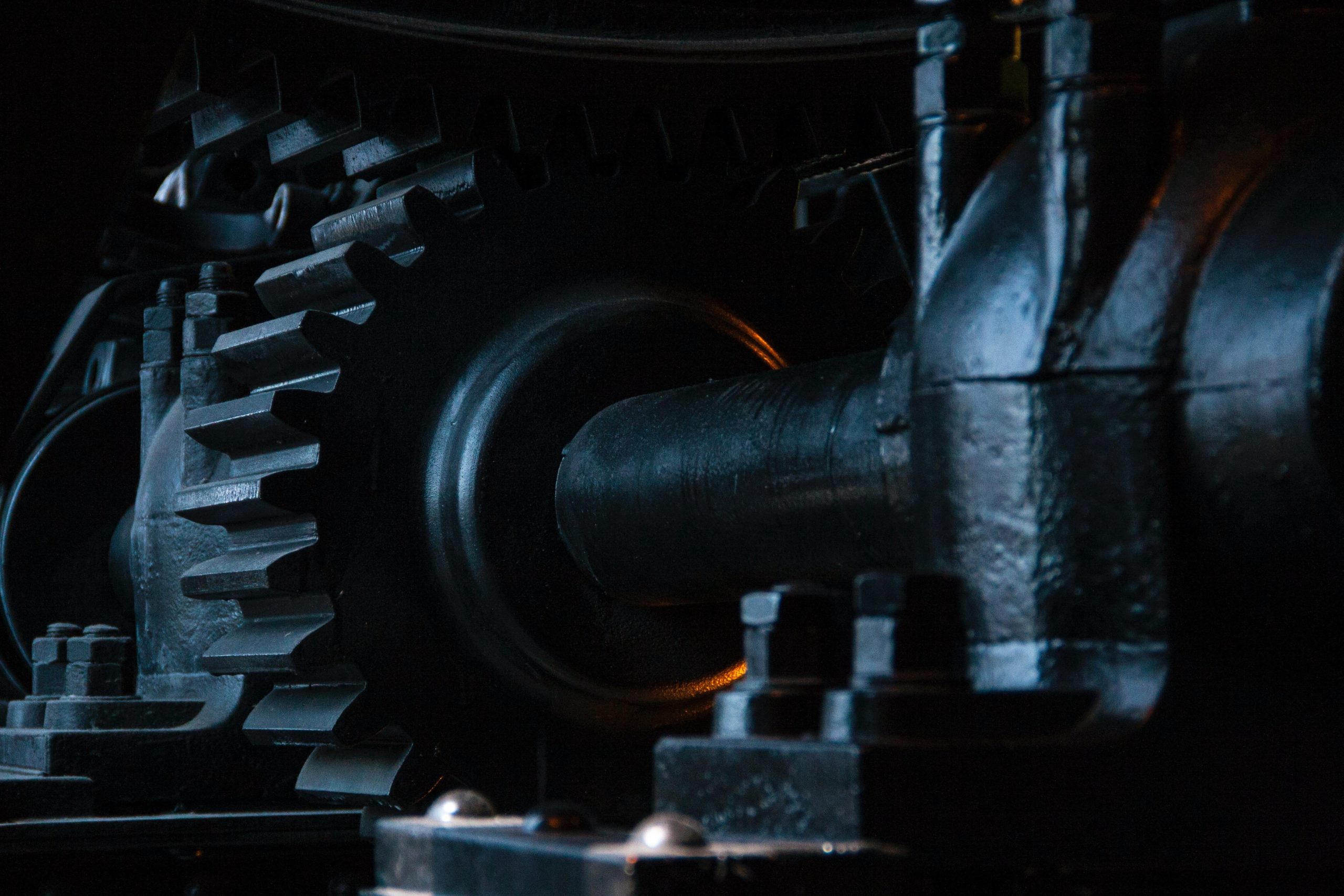

These levers each have long histories of success in fostering innovation and investment, in the energy sector and beyond. With a clear sense of what options might look like, our task in the Energy Futures Policy Collaborative is a complex but essential one: to determine which levers to pull when, how hard to pull, and who should be operating those levers.

To do this, we’re making sure we think both deeply and broadly about how this metaphorical machine might fit together, considering which unintended gears a given lever might turn if we aren’t careful and what unwanted outputs our machine might produce, but also which levers in combination might multiply the force we apply, delivering dividends that ripple across the system.

Marla Orenstein is the Director of the Natural Resources Centre, Canada West Foundation. She is a member of the working group for the Energy Futures Policy Collaborative.